The current collection of Halima Cassell and Emma Rodgers’ sculpture works situated in Bluecoat Display Centre’s exhibition space may, at first glance, seem dissimilar in craftsmanship, yet they are intrinsically tied by their subject matter: nature, and natural forms. Many of Rodgers’ animal works are on display, with accompanying sketches that demonstrate her keen eye for dynamism and fluidity that translate into her sculptural pieces. Their lively stances and the subtle dappling of colour along their forms bring them alive; they appear as if they could run, jump, or take flight at any moment. Even her approach to human figures have bestial elements, whether in their animalistic poses or similar patterning to that of her birds and beasts. In contrast, Cassell’s works do not echo any particular living beings, yet, they are irrevocably organic. Her sculptural works are reminiscent, without being direct mimicries of, a wild array of flora and fauna: bulbs, roots, stems, seed pods. Inspired in-part by mathematical sequences and architectural structures, Cassell’s work occupies the terrain where art and science meet. They reinstate the importance of harmony in nature between tame and wild, death and growth, survival and beauty.

Exhibited together, new narratives are formed from Rodgers’ and Cassell’s existing works. There are not only ecological narratives to be explored in this collection, but also a consideration of the legacy and future of British ceramics. Rodgers and Cassell have similar artistic profiles, both being esteemed female ceramicists, working primarily in the UK but exhibiting around the globe. Ceramics, in the art historical canon, have primarily been categorised as a craft; it is only in the past few decades that it has also been considered a fine art practice. The distinctions between what constitutes as an artform rather than a craft are highly contentious, and often gendered. Crafts, consisting of textiles, woodwork, pottery, and other creative ventures that usually have a utilitarian or functional purpose, have often been gendered. In domestic spaces, textile-making would traditionally be seen as woman’s work, and thus (due to misogyny and classism, among other factors) have been relegated as a lesser artform. Though much of this archaic thinking has all but disappeared today, ceramics still toes the line between being classified as an artform and as a craft. Rodgers’ and Cassell’s work dually celebrates the craftsmanship and artistic value of ceramics. In addition, their work can be seen as a woman’s reclamation of a historically demoted medium and mode of expression.

For a close reflection of their works, I have chosen a piece from each artist that I feel truly represents their approach to subject and form. I will briefly consider how these pieces work separately, and in conjunction together, illustrating the contrasting narratives that link these artists and their work.

Brace of Pheasants by Emma Rodgers

Suspended by leather braces wound tightly around their necks, these two ceramic pheasants represent nature’s visceral side. ‘Brace of Pheasants’ is a display of pure contrast between the sturdy leather straps and delicate ceramic forms. The ceramic pheasants are delicately crafted, with muted tones of turquoise and azure blue colouring their crumpled feathers. The brutality of the scene is punctuated by the bright red spot painted on the face of one of the pheasants, slumped in its leather binding. This piece is taxidermal – without necessitating the deaths of actual birds – in both its subject and display. It stands apart from the rest of the collection with its unusual assembly. This piece defies our expectations for ceramics to be positioned carefully on tables, shelves, or mounted neatly against a wall. Indeed, it defies our need for ceramics to be decorative, pretty; this piece is beautiful, but it is a beauty with a raw edge. Shown alongside Cassell’s work, Rodgers’ ceramic pieces appear more fragile than they are structurally. In this work especially, the delicate bodies of the pheasants evocate a state of death/rebirth that evokes the circle of life in the natural world.

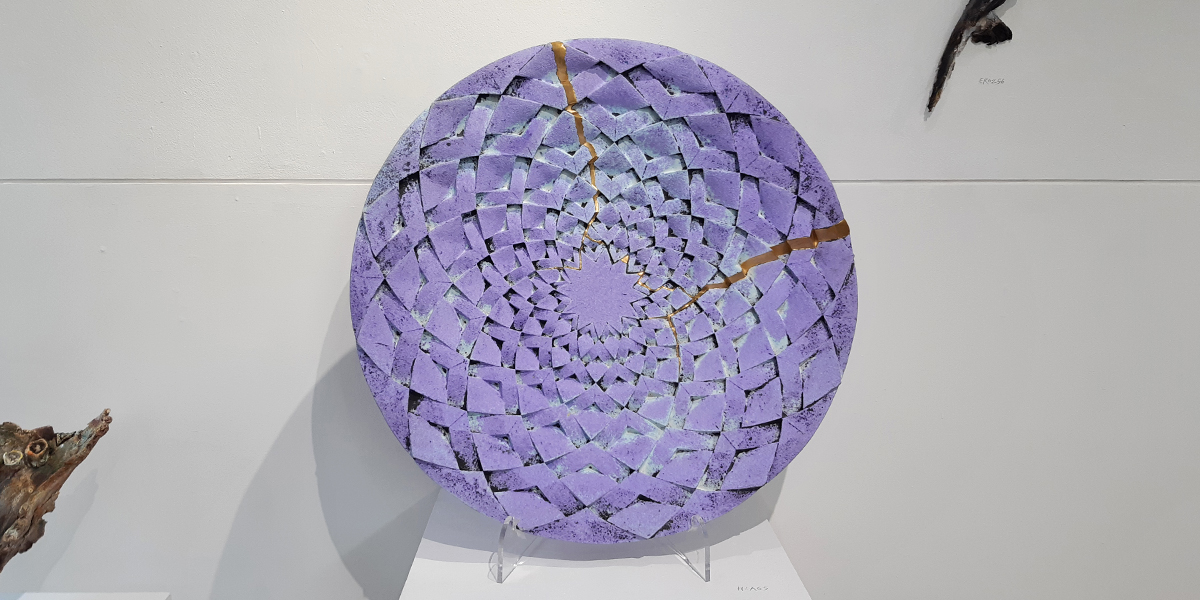

Blue Tapestry by Halima Cassell

Against the prevailing muted tones of the collection, Halima Cassell’s kintsugi inspired work is eye-catching. You can even spot this work in the opening image of this text, peeking out behind one of Rodgers’ peacock. This sculpture appears as if it were woven, with brilliant lilac shapes criss-crossing each other in a spiral formation. From this work, Cassell’s love for maths and architecture is evident. It appears formulaic, each mark carefully considered; yet, the beauty of the material, its colouring and contours, persist. Two bright, zig-zagging gold lines run through the contours of this work like metallic rivulets. In the style of the traditional Japanese art of kintsugi – kin meaning gold, and tsugi meaning join – Cassell has taken a broken work and refashioned it into something brand-new and beautiful. Cassell has stated that she doesn’t mind when pieces break in the kiln, as they will inevitably do on occasion; she understands that there is always a way to salvage the fragmented parts and create a new work of art. Here, the gold mending does not detract from the work, rather, it enhances it. Akin to Rodgers’ pheasants, Cassell’s ‘Blue Tapestry’ marks a process of death and rebirth that imitates processes that are integral to maintaining balance within an ecosystem.